Two years after the death of Mahsa Amini, two Iranian films which defy state censorship and expose the crimes of the Islamic State begin their European rollouts in cinemas. They remind us how fortunate we are to have filmmakers who dare to challenge oppression, misogyny and tyranny.

Two years after a massive protest movement erupted in Iran following the death in custody of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini after she was detained for allegedly violating the dress code for women, mass executions and the violent repression of women continues in Iran.

But so do protests, even if currently limited and methodically crushed by the government. Only on Sunday, 34 female political prisoners went on hunger strike in Teheran’s Evin Prison to mark the tragic anniversary.

Opponents of Iran’s clerical authorities hoped that the protest movements would be a turning point, and the country’s artistic output, while heavily subjected to censorship, shows that they have left an indelible mark.

L’Observatoire de l’Europe Culture delves into two Iranian films that start their theatrical rollouts in Europe and which dare to expose and defy the crimes of the Islamic State in Iran.

The first is My Favourite Cake by Iranian directors Maryam Moghaddam and Behtash Sanaeeha, which premiered at this year’s Berlinale.

The filmmakers behind 2021’s emotionally devastating Ballad of a White Cow were not in attendance for the grand opening of their film in Berlin, as they were banned from traveling by Iranian authorities and had their passports confiscated, facing a court trial in relation to their new film.

In December 2023, local media reported that Iranian security forces had raided the house of the My Favourite Cake’s editor, seizing rushes and materials related to the production.

The country’s hard-line Islamist authorities were believed to have been angered by the film, much like they were for Ballad of a White Cow, which got the directing duo sued by the Revolutionary Guards and charged with “propaganda against the regime and acting against national security”.

Shot in secret around the same time as the Woman, Life, Freedom protests broke out nationwide, My Favourite Cake is a gently subversive film that dares to pepper unexpected radicalism within a poignant tragicomedy.

It follows lonely septuagenarian widow Mahin (Lily Farhadpour), who sleeps in ‘til noon, waters her plants, and goes grocery shopping for luncheon get-togethers with her “old gal” pals. After one such lunch, during which the women debate the utility of marriage and men, Mahin decides to reconnect with the lost freedoms of her youth, now obliterated in an unrecognizable Iran. She yearns to embrace a new shot at happiness and foster a meaningful connection, having lost her husband 30 years ago.

She finds it when she overhears a conversation at a pensioners’ restaurant and sets her sights on divorced taxi driver Faramarz (Esmaeil Mehrabi). She impulsively follows him to the taxi stand where he works and insists he drive her home, brazenly inviting him to spend a stolen evening with her.

While the touching connection between them deepens over food, wine and reminiscing over pre-Revolution Iran, their giddiness is emboldened by a palpable sense of hope. And hope is a dangerous and very fragile thing in Iran…

My Favourite Cake is a lot more critical of the Iranian regime than its story initially seems to suggest, with this nascent romance between two septuagenarians revealing acts of female rebellion. It shows a woman not wearing the mandatory hijab, two people drinking alcohol (illegal in Tehran) and dancing to “un-Islamic” music, but also portraying two unmarried people of the opposite sex alone together.

These acts, while seemingly harmless and not particularly politically explosive to Western eyes, are not just part of a late-in-life romance. They are deeply political.

The biggest subversion is one potent dig at Iran’s morality police, a force that suppresses women’s rights. It comes before Mahin and Faramarz get to spend their illicit evening together. Mahin springs to the rescue of a young woman being arrested in a local park for not wearing her hijab properly.

“You kill them over a few strands of hair?,” responds Mahin, a direct reference for audience members to Mahsa Amini. When she does manage to save the young woman (and avoid being arrested herself for the same crime), Mahin tells her: “You have to stand up for yourself” – a message of empowerment that cannot be tolerated under the nation’s repressive regime.

In its own unique way, My Favourite Cake fizzles with the daring energy of the Woman, Life, Freedom movement, even if it is nestled within a romantic framework that takes a turn for the Linklater-ish in the second half. It is driven by two magnificent performances from Farhadpour and Mehrabi, whose kind faces and joint chemistry make the evening both Mahin and Faramarz share crackle with comedy, joy and poignancy.

But a thing isn’t beautiful because it lasts. The suddenly-dramatic-for-some / gradually-telegraphed-for-others tonal shift leads to a succinct epilogue and reveals the title’s allegorical dimension. By turning the evening’s festivities from joyful to tragic, Moghaddam and Sanaeeh reveal quite how masterfully they’ve set up a subtle but powerful snapshot of how Iranian women really live and a commentary about the harsh realities they face. And what could befall those daring to take control of their lives and destinies.

In February, Berlinale co-heads Carlo Chatrian and Mariëtte Rissenbeek released a statement titled “Call for Freedom Of Movement, Freedom Of Expression for Competition Directors Maryam Moghaddam and Behtash Sanaeeha”, in which they reiterated their fundamental commitment to “freedom of speech, freedom of expression and freedom of the arts, for all people around the world.” The festival directors added that they were “shocked and dismayed to learn that Moghaddam and Sanaeeha could be prevented from traveling to the festival to present their film and meet their audience in Berlin.”

With their heartwarming tale, the directors crossed what they’ve referred to as the Iranian rule’s “red lines”. They knew that there would be consequences, and the censorship from Iran sadly proved them right.

The second film is The Seed of the Sacred Fig, from dissident Iranian filmmaker Mohammad Rasoulof. It was one of Cannes’ most talked about titles this year, a more brazen and outspokenly radical film that examines Iran’s contemporary tensions through a family’s internalization of present turmoil.

Unlike Maryam Moghaddam and Behtash Sanaeeha, Rasoulof was able to present his new film in person. But not without a gripping off-screen story.

The director clandestinely fled Iran two weeks before the premiere on the Croisette. He did so after receiving an eight-year prison sentence for standing up to the brutal theocratic regime. His nail-biting escape led him to Germany to finish the edit of the film, and when the director showed up in Cannes, the response was overwhelming. The Grand Theatre Lumière gave him a moving and lengthy 15 minute plus standing ovation, one which would have carried on had Rasoulof not taken the microphone to thank all those who made the film possible – including the ones who could not make it. He was referring to many of his crew, as well as his two lead actors Misagh Zare and Soheila Golestani. Both are currently banned from leaving Iran, with Golestani having been jailed two years ago amid Women, Life, Freedom protests.

Set during the 2022 protests sparked by Mahsa Amini’s death, The Seed of the Sacred Fig centres on a family of four. Patriarch Iman (Misagh Zare) has earned a promotion after 20 years of loyal service as a civil servant. He will be an investigator, a role that comes with a pistol. The weapon is for protection, as he will be obtaining confessions and signing off death sentences for alleged dissidents.

His wife, Najmeh (Soheila Golestani), is happy for her husband and excited that the new role will lead to a more affluent life for her family. Their teen daughters Rezvan (Mahsa Rostami) and Sana (Setareh Maleki) don’t know what their father does, but are soon clued up, and given a strict set of instructions from their mother. They need to be “irreproachable”, as the slightest slip would have major consequences for their father’s career.

When the daughters’ friend Sadaf (Niousha Akhshi) is hit with buckshot after a school raid, the rule-abiding household begins to unravel. The girls are ready to embrace the freedom they witness in social media videos of the protests, and by implicating their mother in helping Sadaf, a rebellious germ starts to sprout. This is seen on screen in one of the film’s most powerful and upsetting scenes; the camera focuses on Najmeh removing bullet fragments from Sadaf’s swollen face, before dropping them in a pristine white sink. Audiences hear the weight of the buckshot and behold the splatter of blood that stains the basin. It’s an indelible moment that signals that from that point on, there’s no going back.

Things get even more tense when Iman’s gun disappears from his bedroom nightstand and paranoia sets in. Should his superiors find out, he would be publicly shamed and punished with a three-year sentence…

The director’s thriller-infused allegory casts each of the family members as strands of modern Iran. Iman embodies the paranoid totalitarian regime; Najmeh is sclerosed in the role of a conservative-minded but shackled woman, who deep down knows that her daughters’ rebellion represents progress; Rezvan represents change waiting to happen; and Sana realises through her sister’s dissent that she too can no longer “sit down”.

By following the story of these characters who double as cyphers of Iranian society, Rasoulof escalates things from a claustrophobic domestic drama into a thrilling psychodrama with shades of horror, as Sana is cast as the final girl who must free her family.

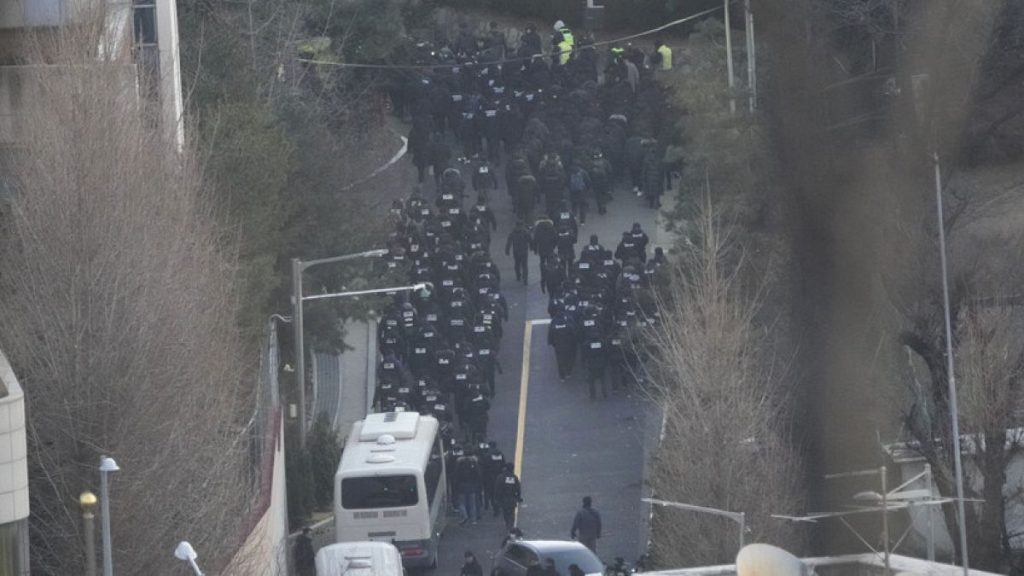

There is no doubt why the film was deemed dangerous by the Iranian government as The Seed of the Sacred Fig exposes Iran’s theocracy as one built on violence and paranoia, and serves as a direct response to the wave of protests after the death of Mahsa Amini. The inclusion of real phone footage censored by Iran’s government is interspersed throughout the film, making Rasoulof’s film a suspenseful thriller as well as a loud call to arms for those who refuse to accept control. Especially when that control is insidiously concealed as familial love.

After its premiere in Cannes, The Seed of the Sacred Fig won several prizes, including the Special Award of the Jury and the Fipresci Award, and it was recently announced that the film will represent Germany at the 97th Academy Awards in the category for Best International Feature Film. Its selection is inspiring not only because of the film’s many artistic achievements but also because it shows how intercultural exchange thrives in open society.

More than that, it will hopefully lead more audience members to grasp to what extent the work from filmmakers like Maryam Moghaddam, Behtash Sanaeeha and Mohammad Rasoulof are not only windows into the crimes of state despotism in Iran but meaningful acts of bravery in the name of justice and art.

Whether a gently poignant romance about the burial of hope in a place where it currently struggles to grow or a more outspoken cry for the old ways to die so that progress can survive, these films take two different approaches to their subversion but are equally radical as acts of artistic defiance. They are, on a purely artistic level, superb films; and when anchored in their socio-political contexts, films that should not be taken for granted. Any cinema or film festival screening them gives a platform to voices facing political oppression, and their release in theatres highlights the fact audiences are fortunate to have filmmakers who dare to challenge oppression, misogyny and tyranny.

They are films reveal that cinema can speak truth to power, and that art often requires creatives to put it all on the line so that voices aren’t silenced.

My Favourite Cake premiered at this year’s Berlinale and is out now in German, Swedish and UK cinemas. It continues its theatrical rollout in mainland Europe throughout 2024, hitting French theatres in January 2025. The Seed of the Sacred Fig premiered in Cannes this year and is released in French theatres this week. It heads to Filmfest Hamburg at the end of this month, as well as the BFI London Film Festival in October.