L’Observatoire de l’Europe

Le soleil représente une source inépuisable pour produire de l’énergie. Les recherches et le développement de la technologie ont permis de maîtriser l’exploitation de sa lumière pour la transformer en électricité et en chaleur utilisables par les usagers. Les panneaux photovoltaïques et les systèmes solaires thermiques captent les photons pour produire du courant. Cette énergie … Lire plus

Intelligence artificielle : quelles perspectives pour le e-commerce européen ?

Le commerce électronique n’est pas moins touché par le développement remarquable de l’intelligence artificielle depuis quelques années. Quelles perspectives peut-on attendre de cette technologie dans le cadre du e-commerce et qu’en est-il de ses limites légales ? L’IA au service …

Wikipedia déclare la guerre aux médias du Groupe Bolloré

Une bataille idéologique silencieuse mais intense se déroule actuellement sur Wikipedia France. Sous prétexte d’évaluer la qualité et la neutralité des médias utilisés comme sources dans ses articles, Wikipedia a ouvert un débat sur les médias du groupe Bolloré. Derrière …

Agents frontaliers américains chargés de prendre des pots-de-vin pour laisser entrer des migrants sans papiers

Les procureurs disent que les deux agents frontaliers du sud de la Californie ont fait un …

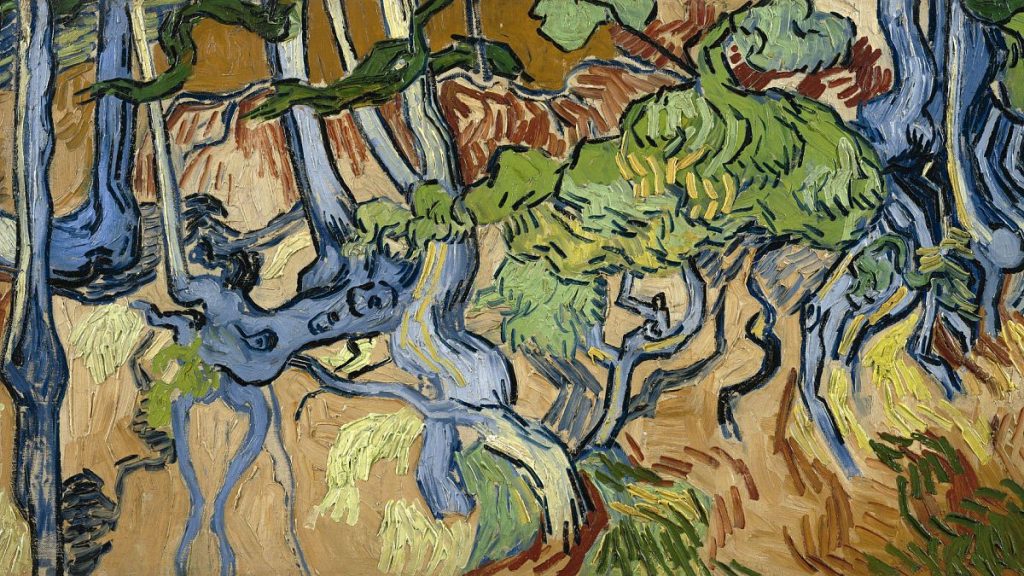

Les règles du tribunal en faveur des propriétaires de maisons en litige sur le site de la peinture finale de Van Gogh

Un couple a combattu les efforts de leur conseil local pour saisir le bord inférieur de …

Tire la rage à travers le Népal, menaçant des villages et des infrastructures clés

Les incendies de forêt ont continué à flamboyer dans certaines parties du Népal, avec un district …